Research

I have worked on projects for a variety of topics, all exoplanet related. As an undergraduate I worked on data reduction of direct imaging data, throughout my graduate program on atmospheric and habitable zone modeling of Earth-like planets throughout stellar evolution, and currently as a post doc on using ozone as a biosignature.

Studying ozone (O3) as a proxy for molecular oxygen (O2)

Molecular oxygen (O2) paired with a reducing gas (such as methane) is regarded as a promising biosignature pair when characterizing the atmospheres of terrestrial exoplanets. However, when O2 is not detectable (for example, at mid-IR wavelengths), it has been suggested ozone (O3), the photochemical product of O2, could be used instead. How reliable O3 is as a proxy for O2 is a very interesting question to me, and one I have been exploring through climate and photochemistry modeling.

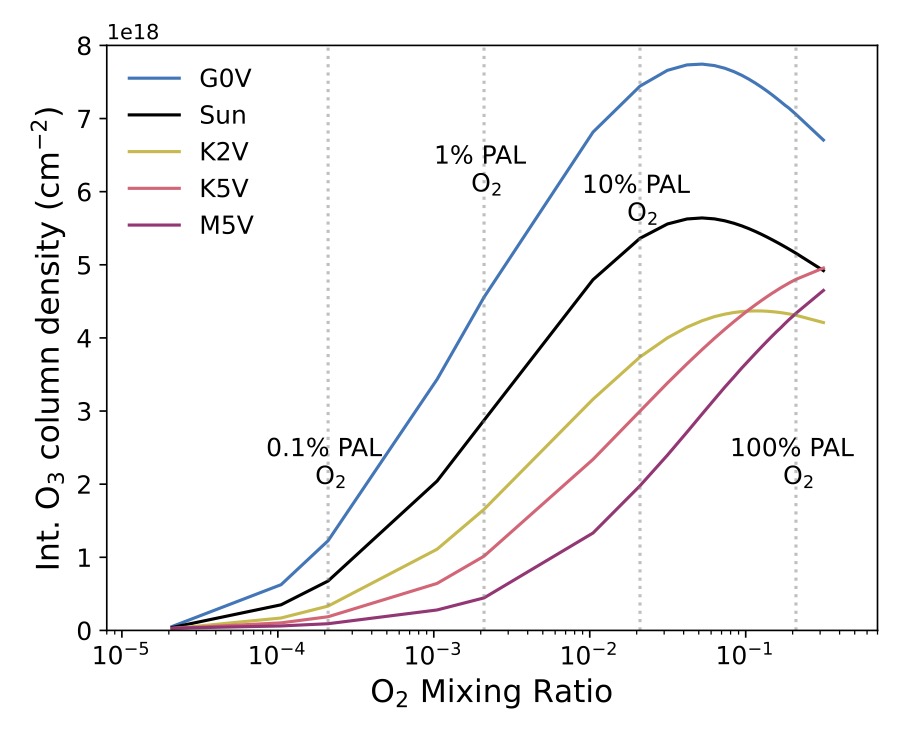

Using Atmos, a 1D coupled climate and photochemistry code I have been studying the O2-O3 relationship around a variety of host stars, as seen in the figure above. The O2-O3 relationship for several host stars is shown, with several different O2 levels in terms of present atmospheric level (PAL) marked as dashed lines. Right away you can see that this relationship varies drastically for different stellar hosts! What I find most interesting is the strange effect seen for hotter hosts where the maximum amount of O3 occurs at O2 levels lower than that on modern Earth. As O2 abundance initially decreases, larger amounts of UV photons capable of O2 photolysis reach the lower (denser) regions of the atmosphere where O3 production is more efficient, thus resulting in these increased O3 levels. This effect does not occur for cooler host stars (K5V-M5V), since the weaker incident UV flux does not allow O3 formation to occur at dense enough regions of the atmosphere where the faster O3 production can outweigh a smaller source of O2 from which to create O3.

Biosignatures throughout stellar evolution

To understand and predict the nature of planetary atmospheres, it is very important to understand their host star! Different spectral types have a wide range of UV emission, changing atmospheric photochemistry. To learn more about the effects of different main sequence stars on habitable Earth-like planets, I would suggest reviewing the work of Sarah Rugheimer.

My focus is not only on how different spectral types affect planetary environments and biosignatures, but also how stars in different evolutionary phases differ from one another.

As seen above, although Sun-like stars spend the majority of their lives on the main sequence, it spends a fair bit of time in other evolutionary stages, where different types of planetary environments could occur.

White Dwarfs

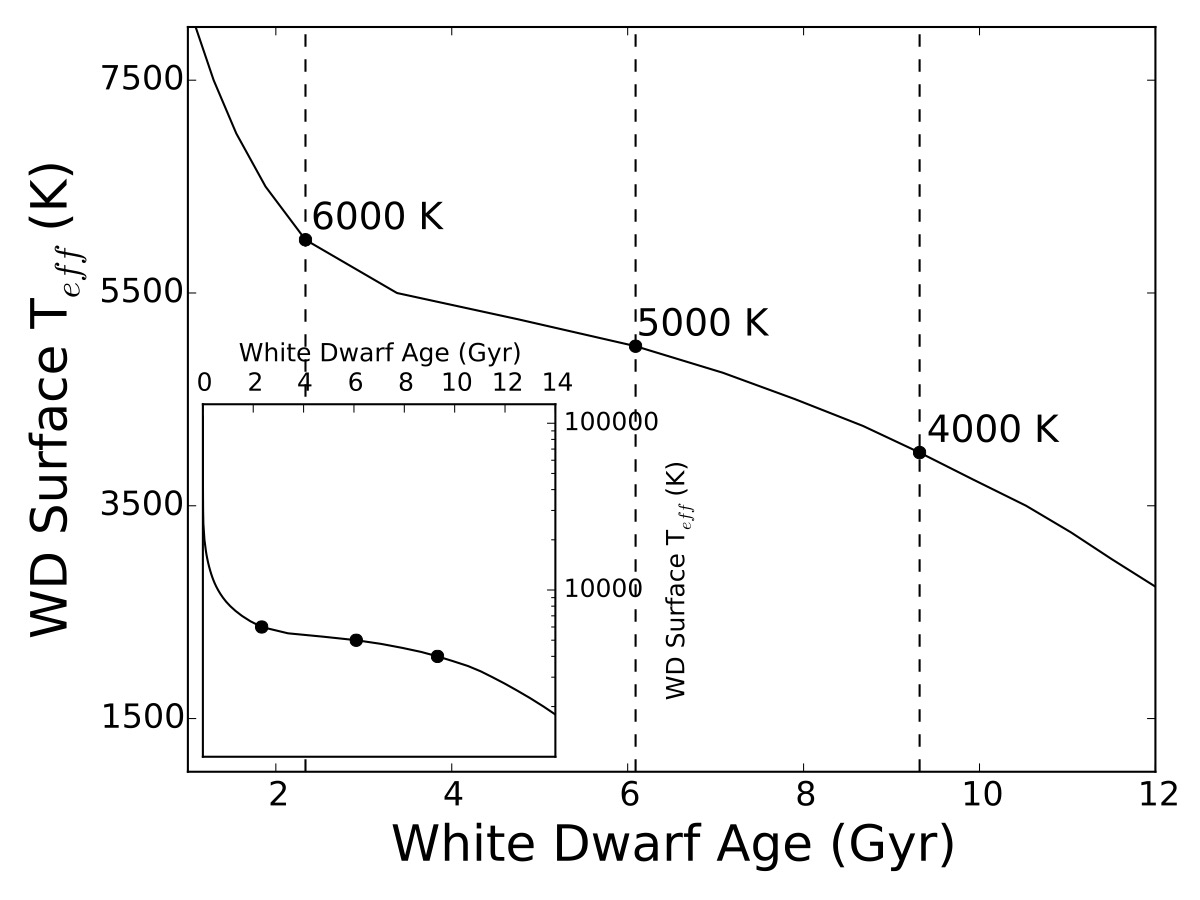

White dwarfs are the end states of stars with core masses of less than 1.4 Solar masses, which comprises the majority of the stellar population. Although they start off being extremely hot, they cool down over time and will eventually have a continuous habitable zone for long enough for life to develop and thrive on a planetary surface.

It takes approximately 10 billion years for a white dwarf to cool down from 6,000 to 4,000 K, giving life enough time to develop and evolve. My work involves simulating the climate and atmospheric photochemistry of Earth-like planets orbiting in the habitable zones of white dwarfs during this period of a continuous habitable zone. Cooler white dwarf scenarios are not included because the Universe simply isn't old enough for those to exist!

Links to my publications on this subject are under the CV page of this site. You can also watch my light-hearted AbSciCon talk on from the early stages of this project here, or my Exoplanets III talk here!

Post-Main Sequence Stars

Habitability throughout the post-main sequence is an interesting scenario because during this phase of evolution the habitable zone is pushed past the original frost line of the planetary system, where over 99% of the system's water is expected to exist!

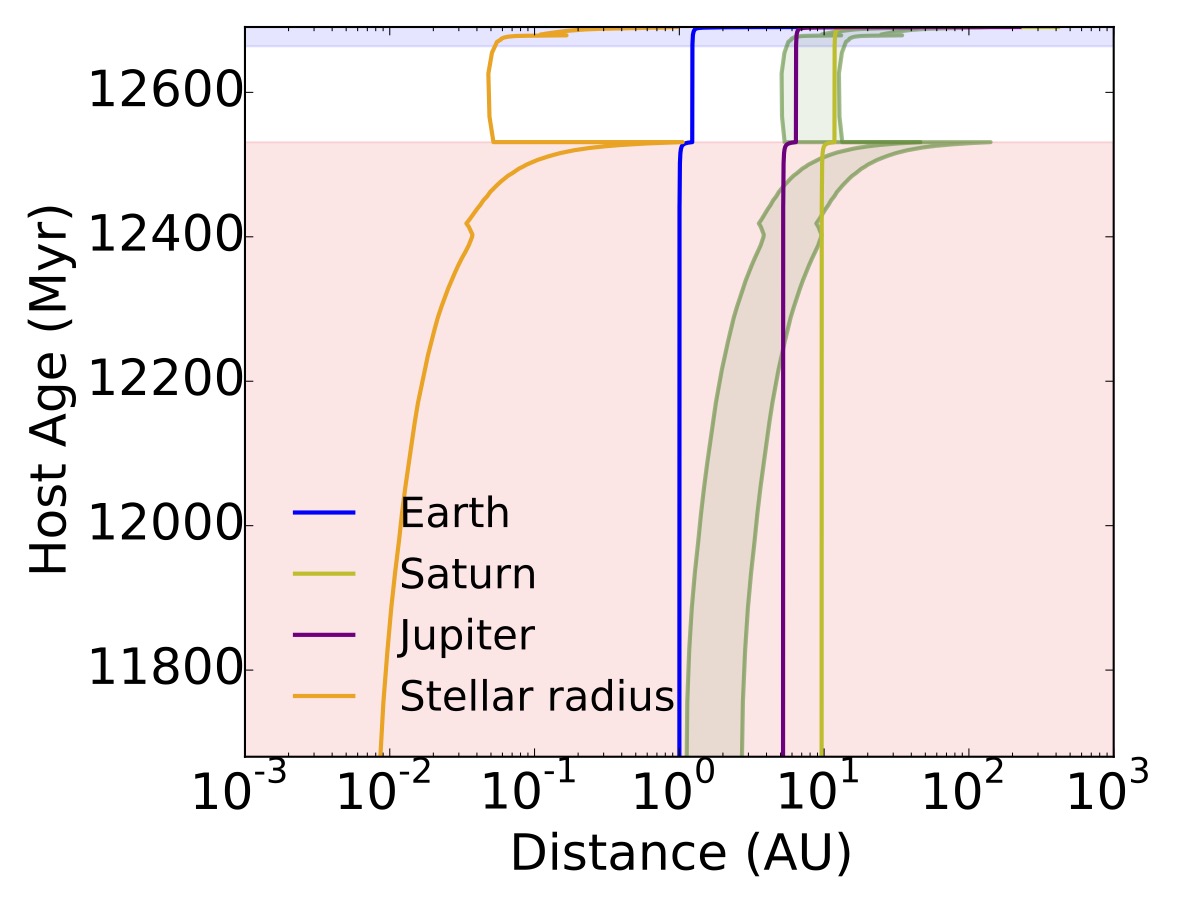

Above you can see the post-main sequence evolution of our own Sun, with the red region corresponding to the red giant branch, the blue to the asymptotic giant branch, and the green the habitable zone. During this time period conditions will not be good on Earth (especially when the Sun's radius grows to our orbital distance!), but the increase in the Sun's brighteness will cause Jupiter and Saturn to enter the habitable zone! At this point in time it will be possible for icy worlds like Europa and Enceladus to melt, potentially exposing previously undetectable subsurface life.

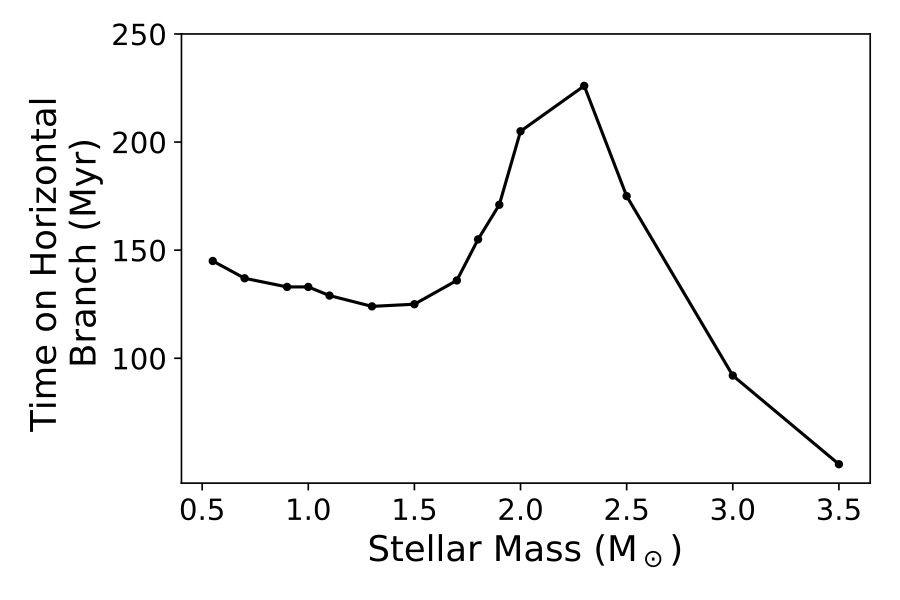

The maximum time a planet can spend continuously in the post-main sequence habitable zone roughly corresponds to the length of the relatively stable horiztonal branch, at which point the star is fusing helium in its core. However, the length of the horizontal branch does NOT depend linearly on stellar mass, as seen in the figure above. While stars like the Sun spend less only about 1% percent of their total lifetimes on the horizontal branch, a 2.3 Solar mass star will spend nearly 30% of its life there. As a result, unlike other habitability searches around main sequence stars where smaller mass stars are prioritized, when thinking about post-main sequence habitability it is best to think of more massive stars. This is additionally convenient since stars the mass of our Sun haven't had quite enough time in our galaxy to reach the post-main sequence!

Links to my red giant publications are under the CV page of this site, and my AbGradCon talk on this project is available here.

Direct imaging around high-mass stars

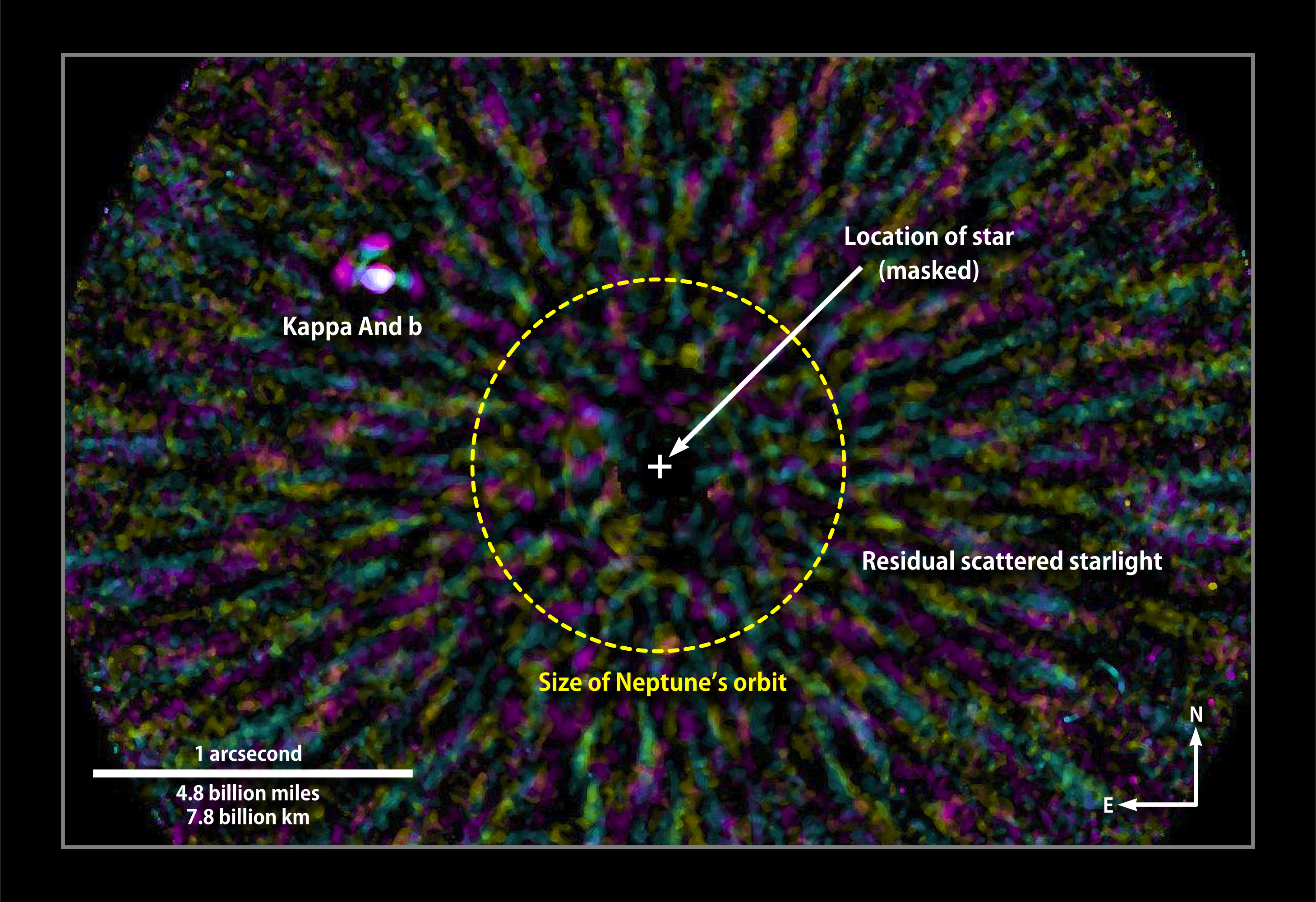

As an undergraduate at the College of Charleston I worked on data reduction for the SEEDS Survey with Dr. Joe Carson. I was fortunate enough to be the first to work on the dataset of the star kappa Andromedae, around which we were able to detect a ~12.8 Jupiter mass companion. The official name of this object is kappa Andromedae b, but as his initial discoverer I fondly refer to him as Derek.

You can watch the mini-Ted talk given by me and the rest of the College of Charleston team here and a brief video made by the college on our research group here.